One of my most precious possessions is a round, painted ceramic cookie tray in the shape of a poinsettia that was given to me by my mother. Every Christmas, this vivid red tray with a yellow blossom in the center has held the sweet holiday treats and candies we’ve prepared to mark this season, so it was especially meaningful when she gave it to me to pass on the tradition.

The holidays are full of traditions and symbolism, and the poinsettia plays a key role at Christmas. But for years, I had no idea that this lovely flower has something to teach us about symbolism and multicultural appreciation.

In fact, how the poinsettia came to the U.S. is an ironic tale of long-ago foreign policy blunders in Mexico. In addition to being a beloved holiday plant, the poinsettia is a reminder of how easy it is for us to appropriate the parts we love of various cultures while not always appreciating the bigger picture or valuing the people from that very culture.

Even as a plant lover and a Latina, I was not aware of the poinsettia’s history for most of my life; I just bought them, like everyone else. With over 2 million poinsettias sold annually, they are the most popular Christmas plant and the best-selling potted plant overall in the U.S. and in Canada, according to Oklahoma State extension — so popular, that every year on Dec. 12, citizens of the U.S. celebrate Poinsettia Day, named so by Congress on July 22, 2002.

Aztec origins

The poinsettia is an Aztec plant. It’s not really a flower. It’s a shrub, says a recent Chicago Tribune article; what we think are flowers are really leaves and the little yellow center is the actual bloom. Indigenous to Southern Mexico, the poinsettia was used by Nahau people as early as the 14th century, long before the European colonization of the Americas.

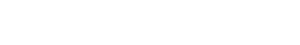

The original Nahuatl name for the plant is cuetlaxochitl (kwet-la-sho-she). People from the Aztec civilization used the leaves to make red and purple dyes and also employed the sap for medicinal purposes.

According to a history of the plant from The Produce News, the plant’s red leaves, known as bracts, were so revered by the Aztec emperor Montezuma that he had them transported to the capital of Tenochtitlan each winter. According to a history of the plant in a Tson News post, in the Aztec culture the cuetlaxochitl represented purity, and the name meant “Flower that withers, mortal flower that perishes like all that is pure.” According to that account, the plant was cultivated as an exotic gift; its intense red represented cuetlaxochitl, the precious liquid of the sacrifices offered to the gods.

Myths and legends

The poinsettia is surrounded by multiple myths and has multiple names. After Europeans colonized Mexico and other Central American countries and spread Christianity, mythology surrounded the cuetlaxochitl and tied it to the birth of Christ. According to Mexican lore, a young girl named Pepita did not have a gift for the baby Jesus – just a humble bouquet of weeds. But angels felt sorry for Pepita and transformed the weeds into brilliant red flowers on the nativity. The story holds that this is why red and green are the colors of Christmas today.

Another legend from 16th-century Mexico asserts that Franciscan friars in the Taxco area witnessed a miracle, where a plain flower was transformed into a beautiful plant with vivid red blooms, and the plant was named Flor de Nochebuena, or flower of the blessed night.

In the following centuries, the Flor de Nochebuena – with its seasonal bloom portending Christmas – became the symbol of the holiday as well as a reflection of Mexico’s colonized past and evangelism.

The poinsettia name has diplomatic ties

So how did it end up with the name poinsettia? Across the globe, the cuetlaxochitl is known as the Christmas Star, Christmas Flower, Mexican Flame Leaf, Lobster Flower, Winter Rose, Crown of the Andes, and Flor de Nochebuena, among other names. Here in the U.S., the poinsettia is named after Joel Roberts Poinsett, who in 1825 was appointed by President John Quincy Adams as the first American minister to the newly independent republic of Mexico.

According to a Washington Post article, “The consipiracy-fueled origin of the Christmas Poinsettia,” Poinsett was a wealthy Southern Unionist and slave owner. He was a world traveler who spoke multiple languages, served as consul general in Chile and Argentina, and had written a widely praised book titled “Notes on Mexico.” Prior to his appointment as Mexican ambassador, he had been appointed secretary of war by President Martin Van Buren.

The Tson News story reports that Poinsett was a nationalist who increased the size of the army exponentially and subsequently transported Native Americans westward in what is now the U.S., saying, “During Poinsett’s term as secretary of war, more Indians were displaced than at any other time.”

Not only was Poinsett not a fan of Native Americans, he was also not a fan of Mexicans, according to multiple accounts. During his time in the country, he failed in an attempt to purchase Texas and took sides in a political dispute. He became embroiled in controversy for meddling in Mexico’s internal affairs, so much so that “poinsettismo” was coined as a term to describe “officious and intrusive conduct.” For this, he became persona non grata and was recalled to Washington, his life in danger – being forced out of the country on Christmas Day.

Poinsett imports and markets ‘Mexican Fire Plant’

Interestingly, Poinsett was also a botanist. When Poinsett arrived in Mexico, he encountered the Flor de Nochebuena on a trip to the Southern town of Taxco in 1828, according to the Oklahoma State extension history. He was so struck by the plant that he shipped specimens back to his home in South Carolina, where the cuttings were propagated. While a nursery owner in Pennsylvania named Robert Buist initially sold the plant to the public under its botanical name, Euphorbia pulcherrima, Poinsett renamed the cuetlaxochitl the much more marketing-savvy “Mexican Fire Plant.” He began to share it with North American growers and it soon became popular.

Poinsett was credited with the discovery of the plant in horticulture journals and made a fortune promoting it throughout the South and eventually worldwide as a symbol of Christmas. Poinsett went on to co-found the Smithsonian Institution, his mess in Mexico largely forgotten. In 1836, Scottish botanist Robert Graham renamed the plant once again — the Poinsettia, in Poinsett’s honor, and the flower’s Mexican identity was further stripped away.

Subsequently, the poinsettia market exploded, all due to an immigrant (irony again).The poinsettia gained even more popularity in the mid and late-1800s when a German immigrant named Albert Ecke made a detour in Los Angeles on the way to Fiji. According to The Produce News, he decided to stay in Los Angeles and bought a dairy and fruit orchard where he eventually began to cultivate flowers, including poinsettias.

By the turn of the century, he’d created an empire. He developed breeding techniques which he patented, eventually monopolizing 90% of the U.S. poinsettia market – which he promoted as a Christmas plant. According to a Readers Digest history, Ecke cleverly sent free poinsettia plants to Hollywood studios and the flower appeared on the sets of programs like The Tonight Show and Bob Hope holiday specials — further solidifying its reputation as the flower of Christmas in homes across the U.S. The company Ecke founded was sold to a Dutch conglomerate Dümmen Orange in 2012, but still controls 70% of the market and sells around half of the world’s supply.

Poinsettias are a multimillion-dollar industry

Sales of poinsettias have not slowed down. Today, according to the 2020 USDA Floriculture Report, poinsettia sales in 2020 totaled $157 million — up 3% from 2019. Along with other poinsettia-related products, the poinsettia industry contributes over $250 million to the U.S. economy overall, says an AgAmerica Lending report.

However, many poinsettia cuttings still come from Central America. An interview with the Hustle on poinsettias describes the supply chain: The breeder harvests cuttings in Central America, where they are put in baggies, boxed and flown to the U.S. in commercial passenger flights. Then, the cuttings are propagated and, when roots form, transported to greenhouses. Growers plant the cuttings in summer and by November they are ready to be shipped to retailers, who strike deals with the growers.

Mexican growers shut out

Despite the lucrative poinsettia industry, Mexican growers have largely been shut out of the market. A century-old foreign soil restriction prevents Mexico from selling the poinsettia – its own native plant – in potted form, the more profitable part of the process.

So what does it all mean? As sales of poinsettias in the U.S. continue to grow, the U.S. relationship with many things Mexican or Hispanic remains rocky. Immigration is controversial and has been increasingly politicized. Both overt and subtle racism against people of Mexican or Hispanic origin continues – for recent immigrants and for individuals whose families have been U.S. citizens for centuries alike.

It seems we love many elements of Mexican and Hispanic culture – the food, the music, arts or style – but are often ignorant of the origins. We often pick and choose what we enjoy from the culture (or any other culture, for that matter) without thought of where things came from, who made or picked it, and who is profiting or who is being left out of the equation.

In the U.S, the overall Hispanic population as of 2022 is now 62.6 million, making people of Hispanic origin the nation’s largest racial or ethnic minority – 18.9% of the total population, according to the U.S. census. Here in my home state of Iowa, the Latino population is also growing. Between now and 2050, it’s estimated that the Latino population in our state will grow from a current 6.8% of the population to nearly 15%.

Even as a Latina with multi-generational roots in the U.S. (albeit from the desert of New Mexico, not home to any tropical flowers), I find myself unaware of many Hispanic cultural elements and histories around me – from the poinsettia and beyond — as the Hispanic population around me grows. When I learn these things, it makes me stop and think again and again about what we’ve taken from other cultures and who gets the credit, and how something as simple as appreciation can be a critical part of inclusion today.

As I decorate my house with poinsettias and take in the sweeping views of the plant in every store, hotel and even church altar, I am struck by the irony that this beloved Christmas plant was appropriated from Mexico. Even here in my small, rural town of Huxley, Iowa, poinsettias are everywhere, not to mention the fact we now have a Mexican restaurant. It’s equally ironic that Poinsett is remembered for a flower he stole from a culture he hated – a flower that earned him a fortune and a day named after him by Congress.

Having referred to the brilliant plant as a poinsettia for so long, I find it hard to switch to calling it cuetlaxochitl (kwet-la-sho-she), but I’m committing. It’s important to call things what they really are. I take in not only its beauty but also its rich history – from its use for healing properties to the mythology surrounding transformation passed down from the Aztecs through conquistadors to today’s Christmas symbolism.

It’s so much more than a cookie tray or ornament, or even a pretty flowering plant by the hearth. The lovely cuetlaxochitl helps us to reflect on our own multicultural legacy – what do we appropriate, unknowingly, without truly appreciating the history and culture from which it came? Where do we give credit? What do we take, and what do we truly give?

And, most importantly, how can we learn to open our eyes and our hearts to others from every culture this Christmas season? Maybe that’s the true lesson and blessing of the pure and beautiful cuetlaxochitl.

This column was originally published by Suzanna de Baca’s blog, Dispatches from the Heartland. It is republished here through the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative.

Mexico Daily Post